European Regulatory Landscape 2020

Introduction

This article gives a high-level overview of the most significant regulatory changes in healthcare products in the European Union (EU) in 2020. The regulatory landscape in 2020 will see the new Medical Device Regulation (MDR) and the new Clinical Trial Regulation (CTR) become applicable, and various Chemistry and Manufacturing Control (CMC) changes. The exit of the United Kingdom (UK) from the EU (“Brexit”) which is likely to happen at some point in 2020 will continue to impact the EU regulatory landscape. This article will discuss and highlight the key elements of each regulatory change.

The MDR, CTR and CMC changes are to be welcomed as they will enhance and build on existing regulations, are designed to keep current with technological and medical advances and help ensure safe and effective medicines and medical devices are delivered to patients. 2020 and beyond will see a changed but much improved regulatory landscape which is robust, transparent and most importantly patient-focused. Engagement and commitment from all stakeholders is required to ensure effective implementation. All stakeholders should apprise themselves of the imminent regulatory changes to determine the impact for their organisations.

At time of writing, the date and manner of Brexit is still unclear. A no-deal scenario will have the greatest impact on the healthcare sector in Europe and the UK. Implications of a no-deal Brexit from the UK’s perspective is the focus of the Brexit section of this article. Brexit information is continually being updated and interested parties can keep up to date with the latest developments via respective government bodies.

EU Device Regulations

Regulation (EU) 2017/7451 on medical devices (MDR) and Regulation (EU) 2017/7462 on in-vitro diagnostic medical devices (IVDR) entered into force on 26 May 2017 with 3- and 5-year transition periods respectively. These new regulations will replace the current directives and represent the biggest change in medical device regulation in the last 25 years. The regulations significantly develop and strengthen the existing regulatory system for medical devices and bring EU legislation in line with technological and scientific advances in the medical device sector. The Regulations are directly applicable at national level without requiring transposition through specific national legislation and should allow for greater legal certainty and prevent variation in the approach taken or in the rules relating to medical devices that are applied across EU Member States3.

MDR

MDR will become fully applicable from 26 May 20203 replacing the existing MDD (93/42/EEC)4and AIMDD (90/385/EEC)5. Until the date of full application devices can continue to be certified and placed on the market according to the Directives with MDD certificates potentially valid until 27 May 20246. The MDR is a 175-page document and contains 123 Articles (10 Chapters) and 17 Annexes. Under MDR, devices within scope of the Regulation are classified as per Annex VIII. Devices are grouped into 4 classes as follows:

-

- Class I: low risk

- Class IIa: medium risk

- Class IIb: medium risk

- Class III: high risk.

Support and Guidance on the MDR is available from the HPRA and EMA websites.

The key changes in the regulation are as follows7:

-

- Scope of regulation extends to all economic operators in the supply chain as well as broadening the range of products subject to the requirements of the regulation.

- Improved performance of Notified Bodies

- Change of classification for some products

- Change of route of conformity for some products

- Increased scrutiny – novel high-risk devices, Class III implantable devices

- Increased control over supply chain

- Additional safety and performance requirements

- Clinical evidence – enhanced requirements

- Post-market surveillance (PMS) requirements

- New requirements – implant cards, UDI and EUDAMED.

Regulation requires that each device has a unique identifier UDI to facilitate the availability of clear information on all of the devices on the market and the ability to identify the manufacturers and other economic operators responsible for them. This information is stored on a centralised database which can be accessed by both the public and healthcare professionals leading to improved transparency8.

In addition to the above changes, improvements have been made to the requirements for economic operators to ensure that products placed on the market are compliant and that there is a prompt response to any issues that arise, such that the integrity of the supply chain is maintained.

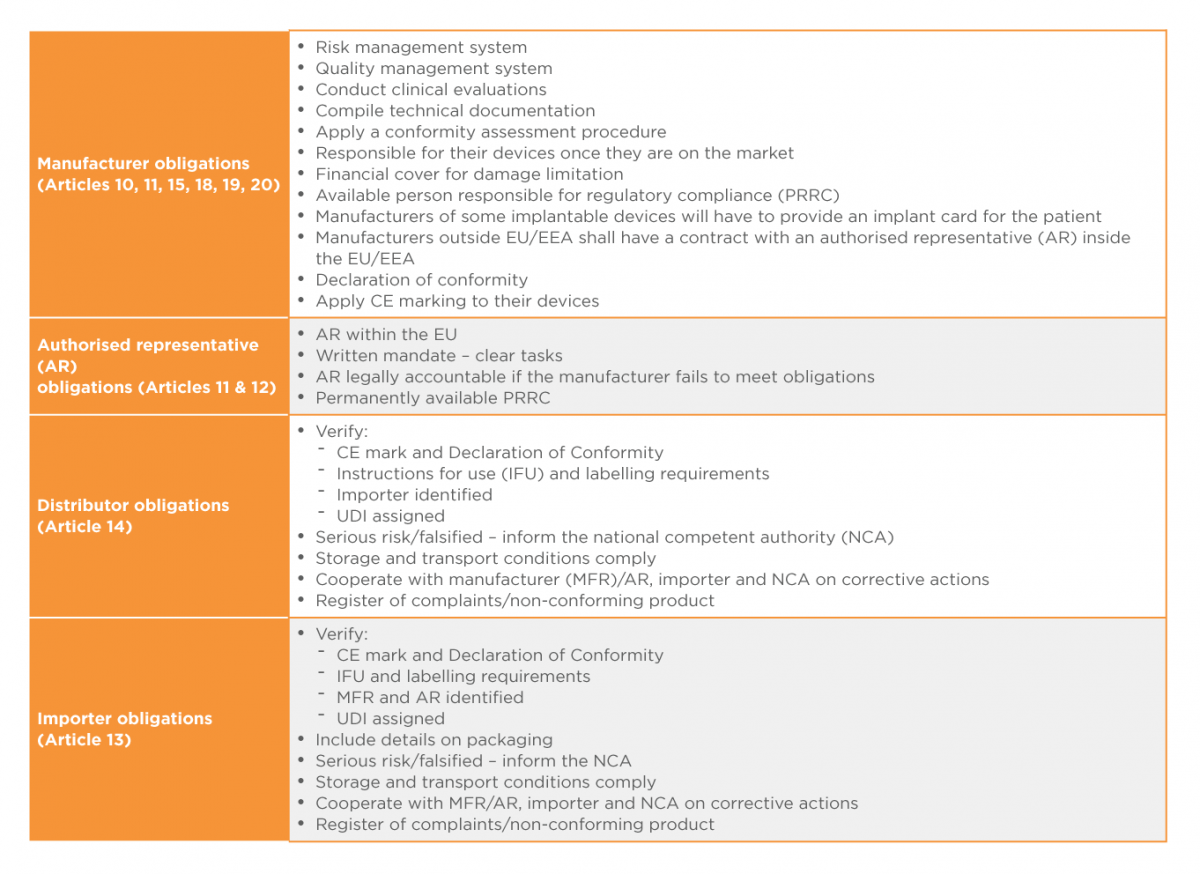

The MDR clearly defines obligations and responsibilities for all economic operators namely manufacturers, importers, distributors and authorised representatives throughout the supply chain. Obligations of manufacturers (Articles 10, 11, 15, 18 and 20), authorised representatives (Articles 11 and 12), importers (Article 13) and distributors (Article 14) are listed in Table 13,7below:

Table 1: Obligations of Economic Operators

It is hoped that the MDR will deliver a more effective, consistent and robust regulatory framework for medical devices across Europe,and afford the public appropriate levels of health protection and access to safe and effective medical devices.

It is hoped that the MDR will deliver a more effective, consistent and robust regulatory framework for medical devices across Europe,and afford the public appropriate levels of health protection and access to safe and effective medical devices.

Clinical Trial Regulations (CTR)

The Clinical Trial Regulation (EU) No 536/2014 (CTR) will change the clinical trial application process currently governed by the Clinical Trial Directive (CTD).

The CTR changes will result in harmonisation of assessment and supervision processes across all EU trials, support sponsors achieving approvals in multiple EU regions with greater efficiency, and protect and improve patient safety. The regulation will adopt the use of the CTIS (Clinical Trial Information System) which will replace the existing EU clinical trial portal and database (EudraCT). 9

Due to difficulties with the development of the new portal’s IT system, it is now likely that the new regulations will only come into force in 2020. As of October 2019, the EMA is monitoring the development of CTIS on a 6-month basis, with business stakeholder input.

Proposed changes as part of the CTR include:

-

- 3 categories of clinical trial studies: clinical trials, non-interventional studies and low-interventional clinical studies.

- Auxiliary medicinal products will replace the existing terminology non-investigative medicinal products (NIMP).

- CTR will allow for the submission of a single application dossier to multiple EU countries, through a single portal controlled by the European Medicines Agency.

- Substantial modifications (replacing substantial amendments) will be similarly submitted through the CTIS portal.

- Suspected unexpected serious adverse reaction (SUSARs) submission process will be simplified, with the submission being made through the EMA database which will then forward on to member states.

- A summary of the clinical trial results must be submitted within one year after completion of clinical trials in all member states, accompanied by a lay person summary.

CMC

This overview of the CMC regulatory landscape in 2020 is restricted to human medicinal products in the EEA.

European Medicines Agency (EMA) Guidelines

Although there has been a slowdown in EMA work on scientific guidelines, due to the move to Amsterdam and other Brexit-related issues, progress on at least some guidelines is still expected in 2020, especially those for which the consultation period ended months or years ago.

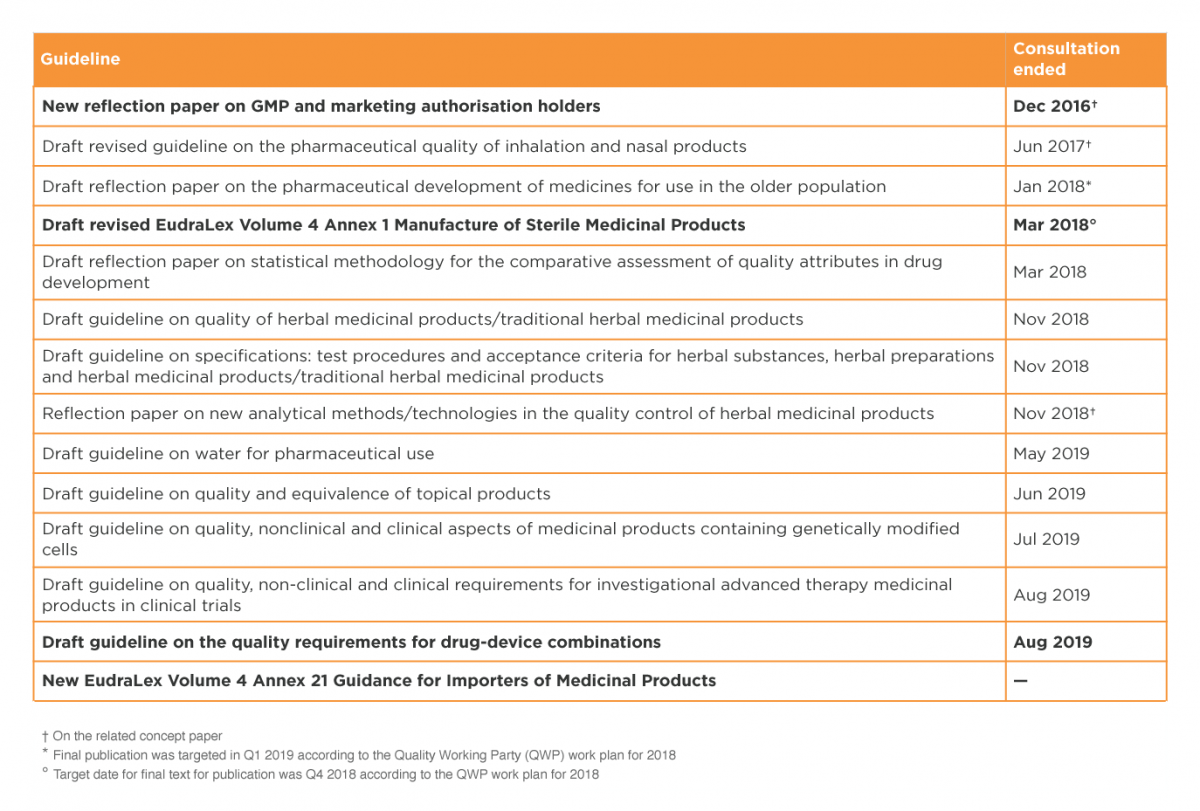

Several pending guidelines of interest are listed in Table 2. Those in bold font, mostly GMP-related, have been highlighted in the EMA Brexit Preparedness Business Continuity Plan10 as meriting higher priority.

The revised Annex 1 to the GMP guide, on manufacture of sterile medicinal products, has been controversial (e.g. see Akers, Madsen and Agalloco11 for a detailed and hard-hitting critique) and it will be especially interesting to see if the problems are ironed out and the annex finally published in 2020.

Table 2: EU guidelines

International Council for Harmonisation (ICH)

International Council for Harmonisation (ICH)

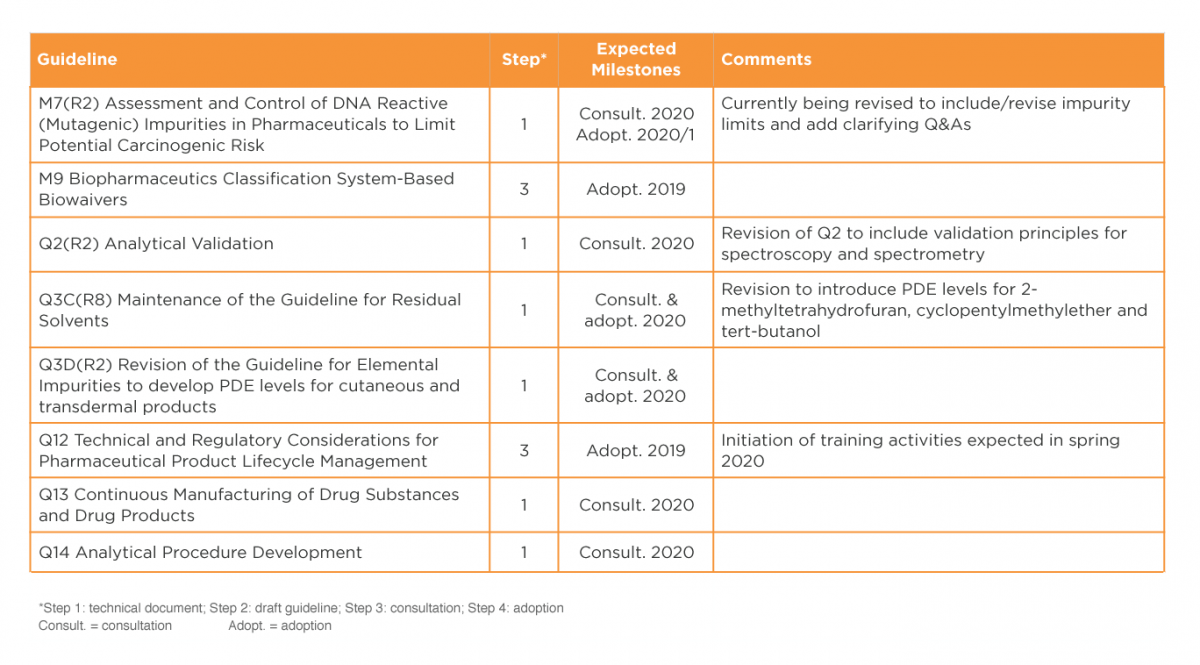

It is expected that work on various draft guidelines will be completed during late 2019 and early 2020, as detailed in Table 3. Several of these guidelines are expected to have significant impact on CMC operations. It will be particularly interesting to observe implementation of Q12 on lifecycle management, and to review the new texts on continuous manufacturing (Q13) and analytical procedure development (Q14). 12, 13

In 2020, the ICH Informal Generic Drug Discussion Group (IGDG) is expected to come up with recommendations on revisions to existing ICH guidelines and a list of proposed guidelines for harmonisation of standards for demonstrating bioequivalence.

Table 3: ICH guidelines

Nitrosamines

Nitrosamines

Nitrosamine impurities have been in the news since mid-2018, when they were detected in angiotensin II receptor blockers such as valsartan. Since then, these probable human carcinogens have also been detected in pioglitazone and in ranitidine. 14

In September 2019, EMA advised MA holders to perform a risk evaluation for each product containing chemically synthesized drug substances, to evaluate the possible presence of nitrosamine impurities. The deadline for the risk evaluations is 26 March 2020. For products identified to be at risk, further confirmatory testing must then be performed, and variations submitted if necessary. The entire exercise must be completed by 26 September 2022. Therefore, it is likely that there will be a lot of regulatory activity linked to nitrosamines in 2020.

Exit of the United Kingdom (UK) from the EU (Brexit)

Brexit is one of the biggest challenges currently facing the healthcare sector. At the time of writing, a deal has not been agreed, however an extension has been granted until 31 January 2020. The outcome of the UK General Election scheduled for 12 December 2019 will, of course, be a major driver in the outcome of Brexit negotiations [at the time the journal went to press, the UK General Election had not occurred yet – EDITOR].

This section provides a high-level overview of the “no deal” Brexit information issued by the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Authority (MHRA); further information and guidance can be found on the MHRA website.

Existing Marketing Authorisations and Marketing Authorisation Applications

It is important that all applicants are registered in the MHRA portals, as post-Brexit, any application made through CESP will no longer be accepted. Applications that are to be submitted to the UK will need to be submitted through the MHRA portals.15

Most human medicines on the UK market already have a UK Marketing Authorisation (MA), and this will be unaffected by the UK exit from the EU. However, most novel medicines and biosimilars, and some generics, come to market via the EMA’s Centrally Authorised Product (CAP) MA route. All CAP MAs will automatically be converted into UK MAs on the day the UK leaves the EU (also known as “grandfathering”):

-

- MAHs will have one year from EU Exit to provide MHRA with baseline data for CAPs that are converted into UK MAs.

- In order to process any variations, MHRA will require the baseline data to have been submitted or,

- MHRA will accept a “basic” baseline data set initially which will enable variations and other post-authorisation submissions to be processed. The full baseline data requirements will still need to be met within one year of EU Exit.

New Marketing Authorisation Applications

MHRA would offer the following new assessment procedures for MAAs for products containing new active substances and biosimilars alongside the existing 210-day national licensing route: 15

-

- Targeted assessment (TA) of new MAAs for products containing new active substances or biosimilars which have been submitted to the EMA and received a CHMP positive opinion, based on submission of all relevant information and the CHMP assessment reports to MHRA. MHRA review will be completed within 67 days of submission of a valid application to the MHRA.

- Full accelerated assessment, that industry can choose for new active substances, with a timeline of no more than 150 days.

- “Rolling review”, for new active substances and biosimilars, which would allow companies to submit an MAA in stages, throughout the product’s development, to better manage development risk.

Clinical Trial Applications and substantial amendments to a trial

The MHRA will take on the responsibilities for clinical trials in the UK currently conducted under the EU system. 15, 16 The UK will continue to recognise existing approvals, both for regulatory and ethics. Guidance has been issued covering significant amendments to a clinical trial; this and further information on import licensing, safety reporting and publishing of trial results can be found on the MHRA website, briefly:

-

- Location of Sponsor: The UK would require the sponsor or legal representative of a clinical trial to be in the UK or in a country on an approved country list which would initially include EU/European Economic Area (EEA) countries.

- Regulatory requirements for running a trial: The UK’s current regulatory framework will remain in force after a no deal. The EU Clinical Trial Regulation will not be in force in the EU at the time that the UK exits the EU and so will not be incorporated into UK law on the exit day.

- Regulatory requirements for Investigational Medicinal Product (IMP) for trials: For IMPs coming into the UK, the UK will recognise Qualified Person certification done in an approved country (initially EU/EEA countries).

Conclusion

The landscape of regulatory activities in 2020 is marked by changes in all healthcare sectors; medicines, medical devices and clinical trials. The objective of the regulatory changes across medicines, medical devices and clinical trials is to provide a robust, transparent and efficient regulatory framework that will deliver safe and effective innovative healthcare products to patients as quickly as possible. Medical device companies, MAHs and sponsors of clinical trials must develop strategies to adapt to the imminent changes with supports available from Competent Authorities, Notified Bodies, European Council and the EMA. Brexit will also impact the healthcare sector and companies should access the array of Brexit guidance documents available in particular from Competent Authorities on the possible Brexit outcomes to assess the implications for their product(s) and organisation.

References

- Regulation (EU) 2017/745 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2017 on medical devices, amending Directive 2001/83/EC, Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 and Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 and repealing Council Directives 90/385/EEC and 93/42/EEC

- Regulation (EU) 2017/746 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2017 on in vitro diagnostic medical devices and repealing Directive 98/79/EC and Commission Decision 2010/227/EU

- Health Products Regulatory Agency (HPRA)Website New EU MDR/IVDR Legislation. Available from:http://www.hpra.ie/homepage/medical-devices/regulatory-information/new-eu-device-regulations

- Medical Device Directive (MDD) Council Directive 93/42/EEC of 14th June 1993 concerning medical devices.

- Active Implantable Medical Device Directive (AIMDD) (90/385/EEC) Council Directive 90/385/EEC of 20 June 1990 on the approximation of the laws of the Member States relating to active implantable medical devices

- European Commission. Factsheet for Manufacturers of Medical Devices. European Commission; 2018.

- Health Products Regulatory Agency (HPRA )Website. HPRA Publication New EU Device Legislation Information Pack. Available from:http://www.hpra.ie/homepage/medical-devices/regulatory-information/new-eu-device-regulations

- Health Products Regulatory Agency (HPRA) Website: Key aspects of the Regulations for Medical Devices and IVDR’s .Available at http://www.hpra.ie/homepage/medical-devices/regulatory-information/new-eu-device-regulations/key-aspects-of-medical-device-regulation-(mdr)-and-common-(in-vitro-diagnostic-medical-device-regulation)-ivdr-aspects

- Regulation (EU) No 536/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 April 2014 on clinical trials on medicinal products for human use, and repealing Directive 2001/20/EC.

- EMA Brexit Preparedness Business Continuity Plan, Phase 3 implementation Plan, 9 October 2018

- Akers JE, Madsen RE, Agalloco JP: Annex 1 Misses the Mark – Expanded Version. Pharmtech.com, 14 March 2018.

- Brennan, Z. ICH Updates: What’s Coming in 2019 and Beyond. Regulatory Focus, 29 April 2019

- International Council for Harmonisation www.ich.org

- European Medicines Agency. EMA advises companies on steps to take to avoid nitrosamines in human medicines [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/ema-advises-companies-steps-take-avoid-nitrosamines-human-medicines

- Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Authority. 2019. Further guidance note on the regulation of medicines, medical devices and clinical trials if there’s no Brexit deal.

- Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Authority. 2019. Guidance on substantial amendments to a clinical trial if the UK leaves the EU with no deal.

- Regulatory Rapporteur – Vol. 17, N0 1, January 2020.